Looking after and conserving family documents

Demobilization account from 1918

The stories told by a first world war soldiers de-mob paper

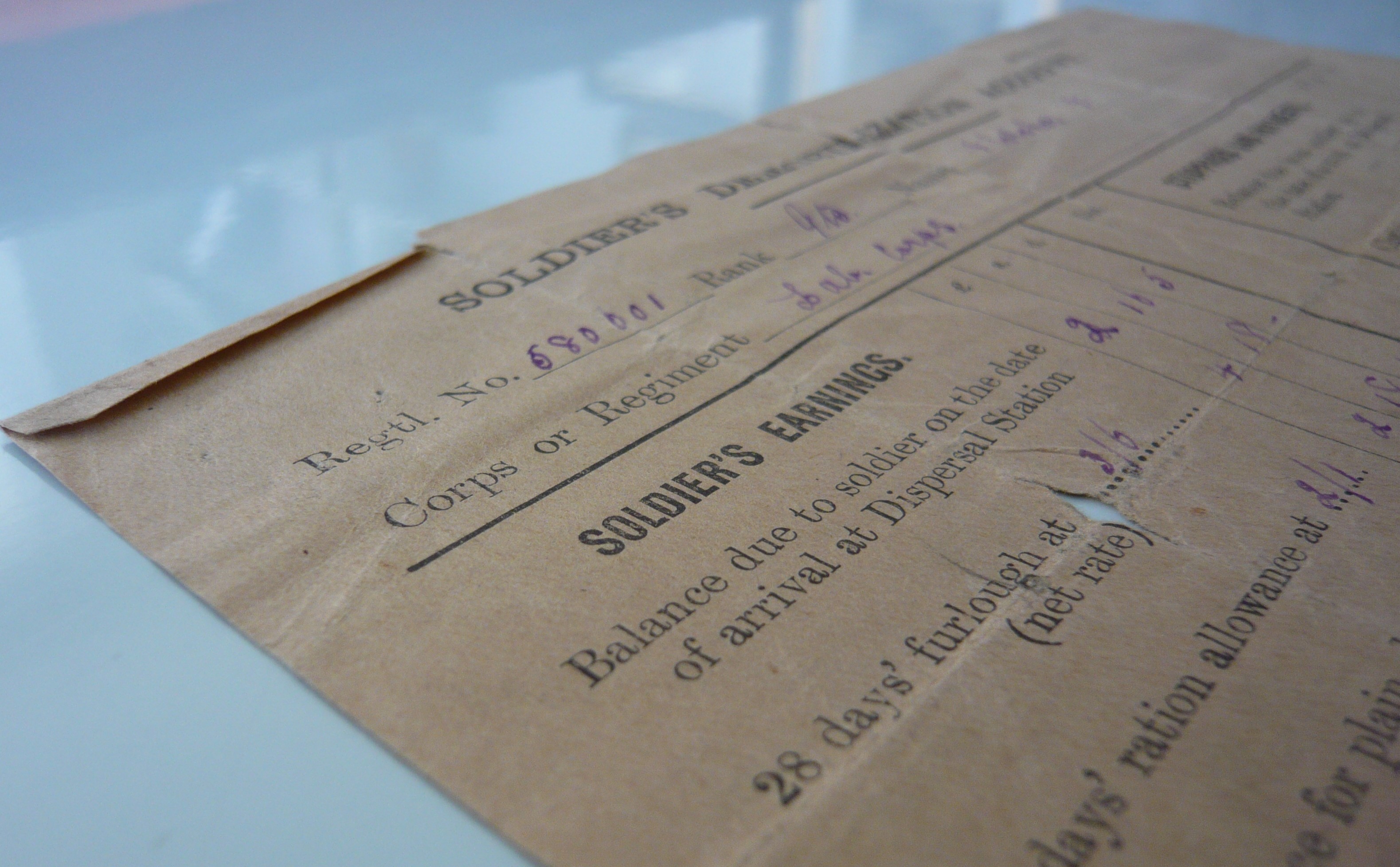

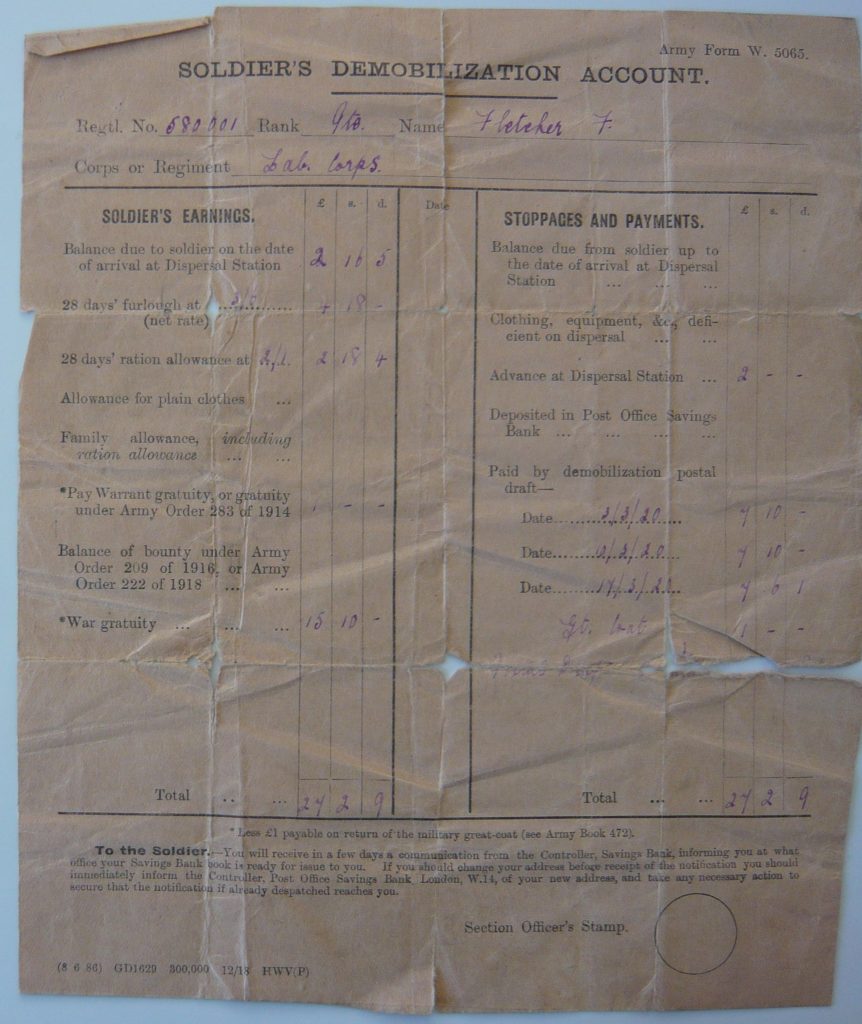

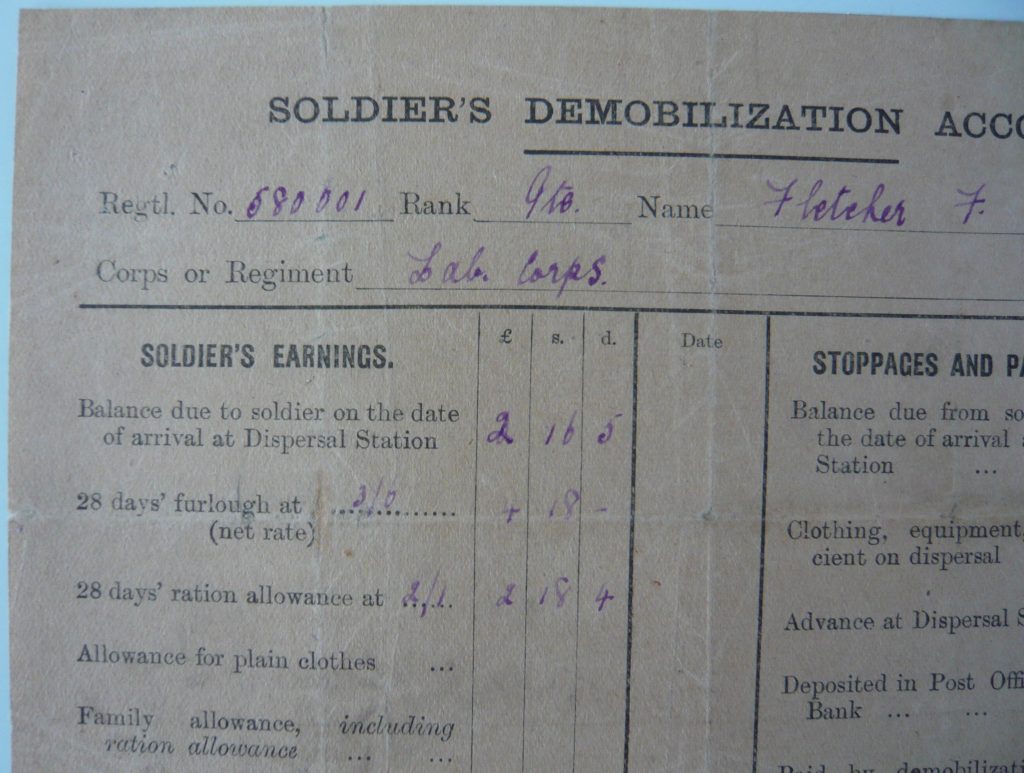

This interesting piece of paper arrived in the studio in the Autumn of 2020. A soldiers demobilization account belonging to the father of the current owner. A father who said very little of his wartime life.

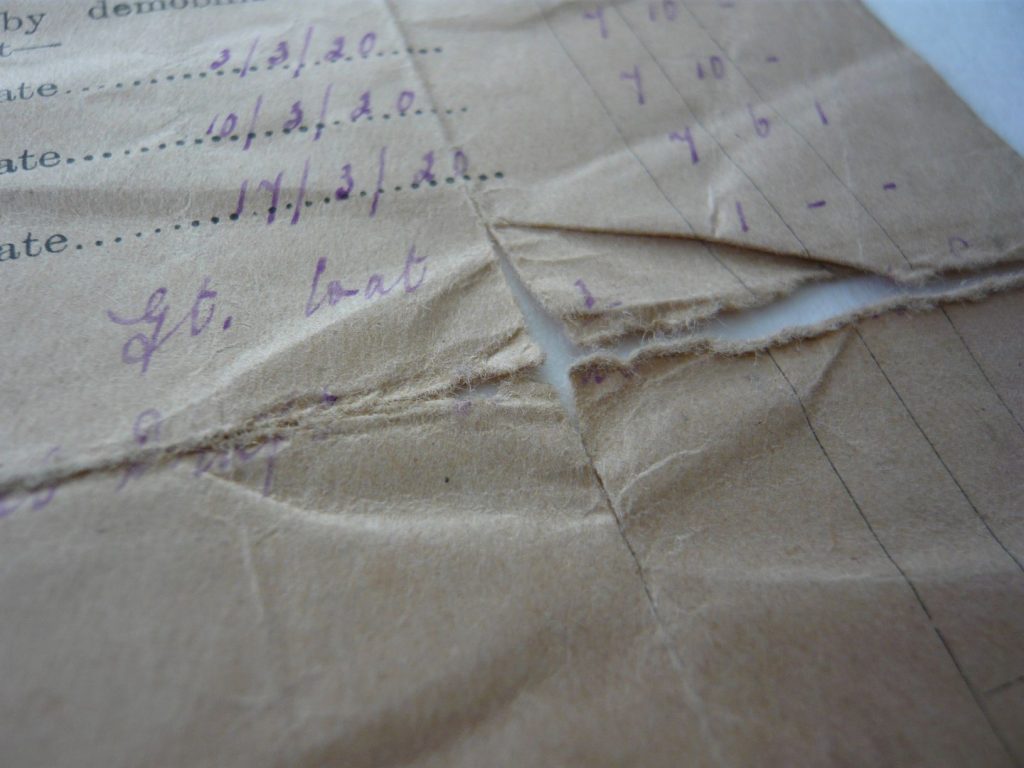

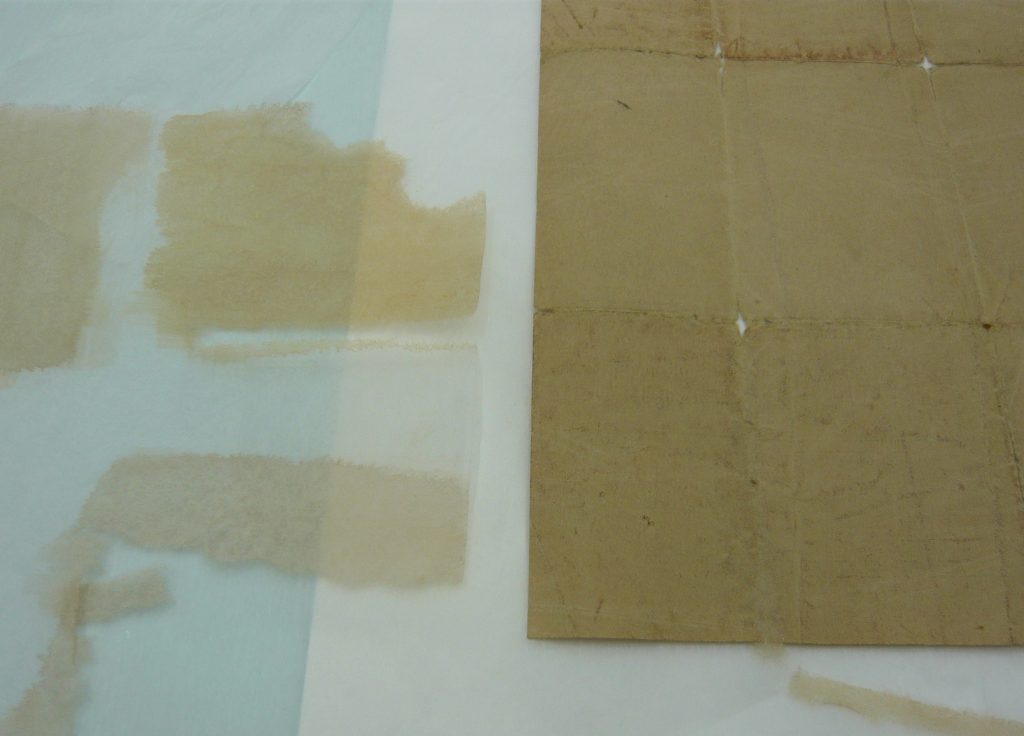

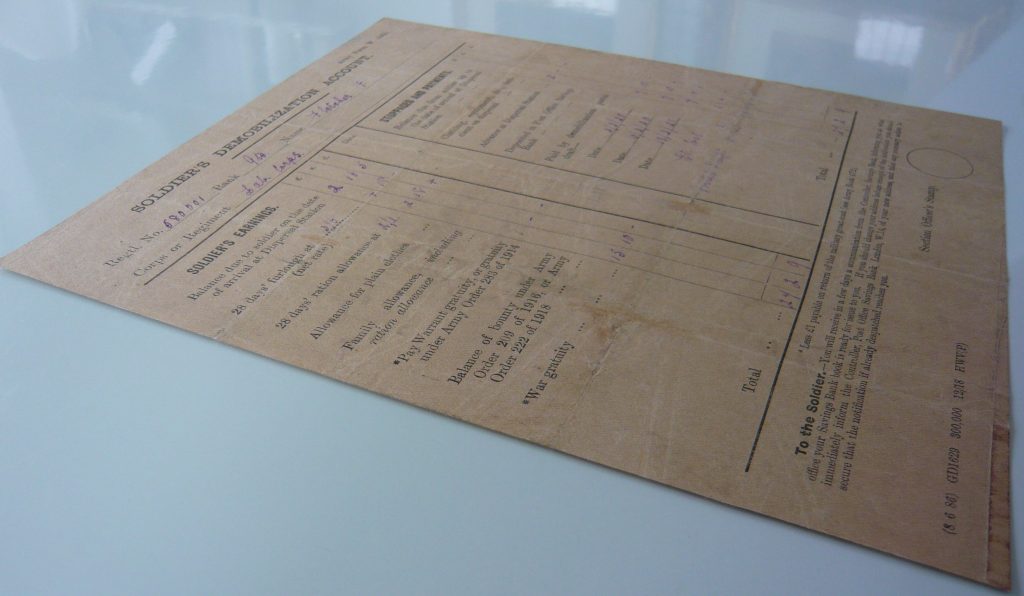

My brief was to repair the document and preserve it for the next generation. It is made from very fragile paper, very soft and torn along the folds. The weak paper shedding fibres along the tears. Repairing would hold the paper together consolidating the paper and the fibres preventing more from detaching and being lost.

After a little surface cleaning I was able to press the document flat and repair the tears using toned tissue paper and wheatstarch paste.

The result is the paper is held together and more of the writing is now visible.

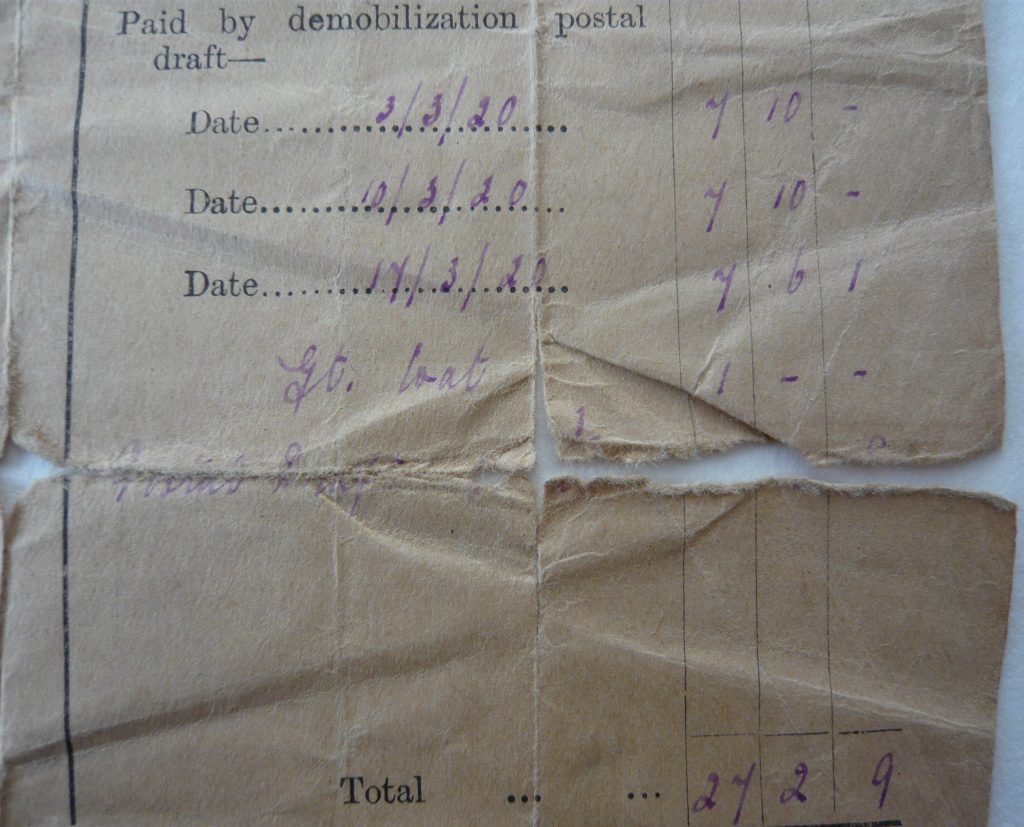

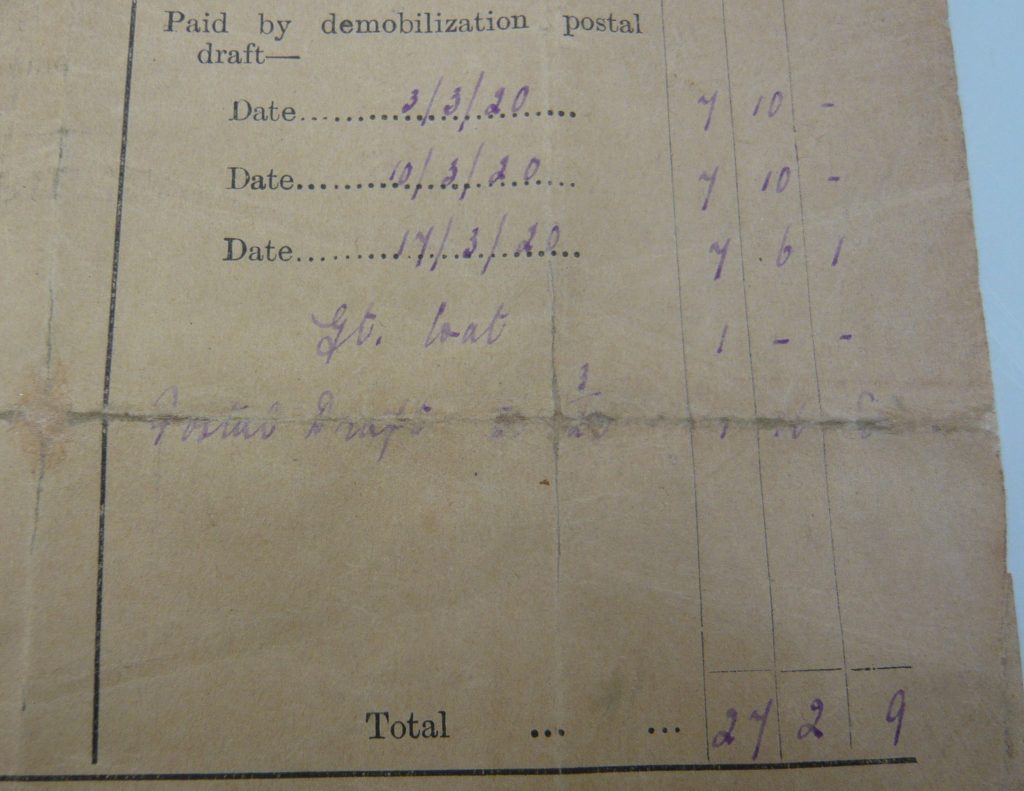

Documents like these are a tangible link to family members, their lives and stories. I was amazed to see the term furlough used in 1918, something, like for everyone, I had not come across until the events of 2020. It was also pointed out to me about the section concerning a charge of £1.00 for his greatcoat; soldiers were expected to return the coat to the nearest railway station after their return home when their £1.00 would be reimbursed – quite a lot of money at that time.

I love my job and the practical side of conservation treatments – but even more, I love the stories behind the objects I treat. The fascinating history and tales are there to be discovered and shared.

This document inspired the owner to write a short story based on the life of this soldier. With kind permission I can share it with you here (Copyright Gwen Goodhew 2020)….

The End of Great Grandad’s War 1920

by Gwen Goodhew

He’s at the back of the wave, washing the unwashed soldiers into the carriages. Private Fred Fletcher slams the compartment door behind him and clambers over the hillocks of backpacks and tin helmets, seeking a crevice. He’s assailed at once by the pungent stink of closely confined soldiers. Sliding past Higgins, the squad bully boy, and into the corridor, he makes for a carriage door, and backs his frail frame against it, ignoring the mumbled protests of those he shoves aside. There’s nowhere for his kitbag except between his feet so he wedges it there. Once stable and warmed by the bodies around him, he re-lights a stub of Woodbine, that he has been holding cupped in his hand. He stretches his neck and blows smoke through pursed lips at the ceiling. His taut shoulders relax as the nicotine wafts through him. He allows himself to drift off in the fug until there is a warning heat in his fingers. Turning, he tugs at the leather window strap and flings the stub out into the blackness.

“Close that bloody window, mate!”

He grunts an acknowledgement as he pulls up the window and secures the strap on its stud, then resumes his position with his back against the door, hands thrust deep in his greatcoat pockets. His fingers find and draw out a thin piece of paper, which he unfolds and reads. A derisive snort escapes him – his Soldier’s Demobilization Account – five years of his miserable life reduced to two columns of figures!

“Stoppages and Payments,” he sneers. “Greatcoat – one pound. What are they going to do with these rags? Save’em for the next bloody war? Miserable buggers!”

“T..t…to ri.ri.ri.right, mate.”

Fred turns, surprised, to the big sapper, whose body is pressed against his. For the first time, he sees the tremor in his hands and the twitch in his jaw– another one damaged forever by this madness. He looks down at himself, at the coat that hangs on him like a threadbare elephant skin. He will have to hand this in at a railway station if he wants to get his money back, but right now he is surprised by how reluctant he is to do this. There must still be lice in the seams – the familiar itch is coming back even though the coat and everything else was fumigated in Aldershot. But he feels safe inside it and he needs its warmth. He was always thin but since being injured, he’s just a walking skeleton.

He gulps over and over again, trying to fight off memories and a panic attack. Every day for three years, whatever the weather, he wore this coat. When the gas got him, his greatcoat had clung to him as he sank down the side of a foxhole, coughing and gasping, eyes sore and oozing, waiting to die. He might have died, too, if it hadn’t been for the little warmth provided by the coat. It kept him alive until he was dragged out under cover of darkness. Then there was the time he snagged his leg on barbed wire and it went nasty. Fever ravaged him for days and he lay, shivering, against the trench wall wrapped in his coat. He shakes his head, trying to dislodge the images there. They shipped him back to the hospital in Blighty, but they didn’t let him stay long. At least, he landed a job as batman to the colonel when he returned to the front. It was worth a bit of bowing and scraping to keep out of the fighting.

His coat’s pockets hold other treasures. He runs a finger along the smooth casing of his penknife, finding a ridge that opens the longer blade. A glimmer of a smile twitches his lips as he imagines his ma’s reaction if she had seen him using that same blade to cut up his dinner and to dig out a bullet from a mate’s leg. His other hand finds a coil of thin string. Civilians have no idea how valuable string can be when you have nothing else.

There is another piece of paper too, greasy and torn from constant re-reading – a short stiff letter from Dolly, the girl he hopes to marry. His mate, Dick, had brought his sister to see him when he was in hospital. Fred flinches as he remembers the disappointment in her eyes when she looked down at him – a feeble wreck of a man, who found it difficult to speak and almost impossible to smile. She had promised to write but he had to wait nearly three months before the letter arrived. Perhaps he is just being a dreamer, but he needs a dream after what he has seen – and done. And she probably needs a husband. Men are in short supply.

“All out! Getta move on. It’s Brummagem-on-Sea for you lucky boys.”

A half -hearted cheer goes up. The train lurches backwards and forwards as it draws into New Street Station. Men fall over each other, eager to leave. Fred stumbles onto the platform, a stabbing pain from his wounded leg taking him by surprise. Then tossing his kitbag over his shoulder, he starts the slow walk back home. There is little to look forward to. His mother and younger brother died from Spanish Flu a few months ago. His brother, Jack, is so maimed that he will never be able to carry on in the music hall. The heart has gone out of the family. He stops, lights another Woodbine, draws his coat tight around him and sets off again.